The last time Oregon signed the highest-rated recruit out of California, the circumstances were eerily similar to the De’Anthony Thomas coup this year.

Like Thomas, this athlete wanted to attend a school with a great track and field program. He’d originally made a verbal commitment to an established football powerhouse, but almost immediately had his doubts.

His decision to change schools at the last minute stunned the football world.

The local newspaper declared his choice to attend Oregon the #2 sports story of 1982.

It all turned out to be what’s recently been called “the greatest false alarm in football recruiting history.” Because he wasn’t just “Mr. Football” in California; he was considered by many the #1 player in the nation, and winner of multiple national HS Player of the Year honors.

A recent issue of ESPN The Magazine profiled the last 25 players named #1 in their high school recruiting classes. With very few exceptions, they all went on to at least reasonable success in college and life. Many continued on to NFL superstardom. If the story had gone back five more years, the authors would have found perhaps the most spectacular recruiting flameout of all time.. and a media frenzy that angered his coach even after the player left school.

Kevin Willhite’s story is a cautionary tale for recruiters, coaches, and fans everywhere.

**

Recruiting

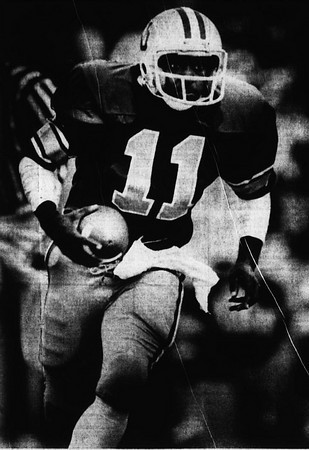

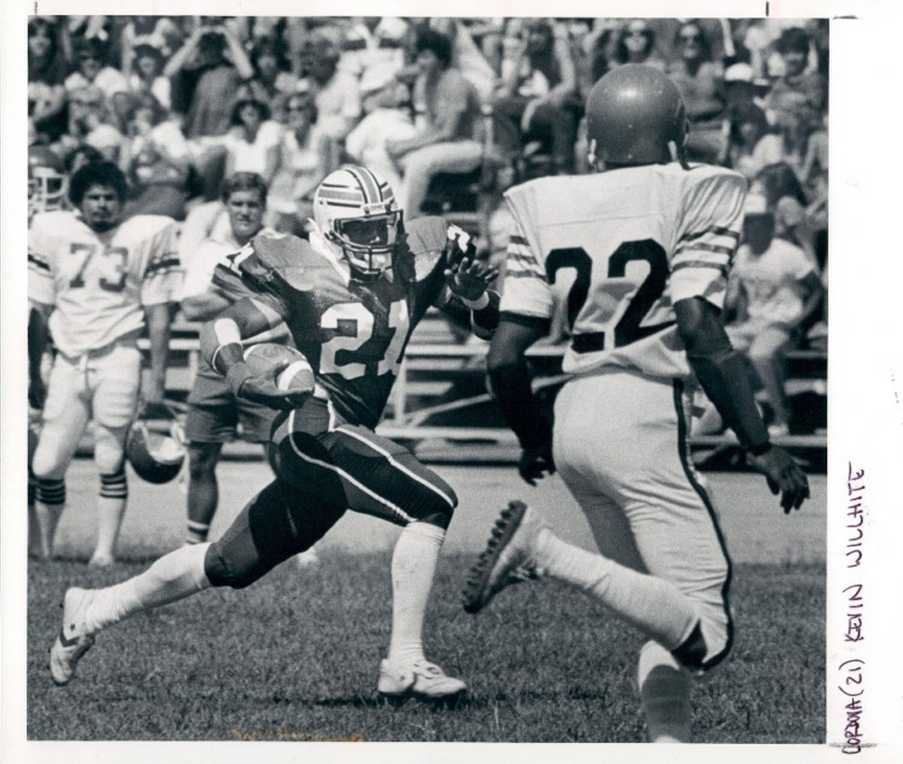

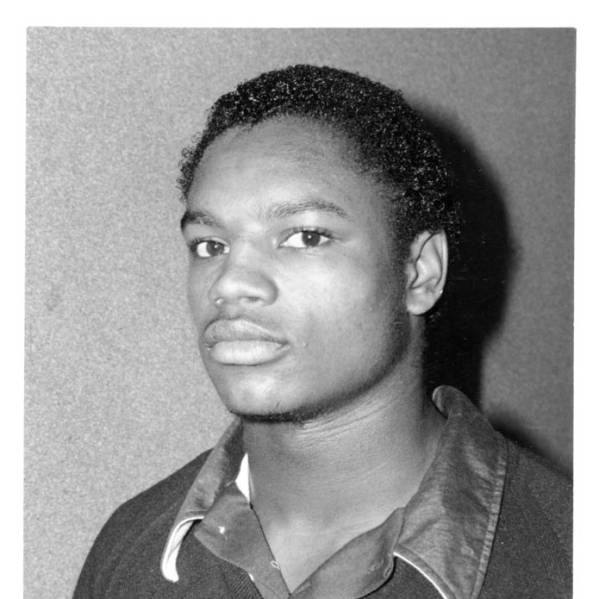

Running for Rancho Cordova, 1981Willhite, a quick and strong tailback out of Rancho Cordova High in Sacramento, had rushed for almost 5000 yards and 72 touchdowns during his prep career. He was named national HS player of the year in 1981 — over Bo Jackson and Marcus Dupree, no kidding — and, as a consensus All American, had offers from “over 500 colleges,” which meant there must have been some very optimistic D-III coaches out there. He had good genes; his brother was Gerald Willhite, who had just finished a stellar career at San Jose State and went on to a solid career at Denver as a first-round draft pick, and his cousin was Bears legend Gale Sayers.

Running for Rancho Cordova, 1981Willhite, a quick and strong tailback out of Rancho Cordova High in Sacramento, had rushed for almost 5000 yards and 72 touchdowns during his prep career. He was named national HS player of the year in 1981 — over Bo Jackson and Marcus Dupree, no kidding — and, as a consensus All American, had offers from “over 500 colleges,” which meant there must have been some very optimistic D-III coaches out there. He had good genes; his brother was Gerald Willhite, who had just finished a stellar career at San Jose State and went on to a solid career at Denver as a first-round draft pick, and his cousin was Bears legend Gale Sayers.

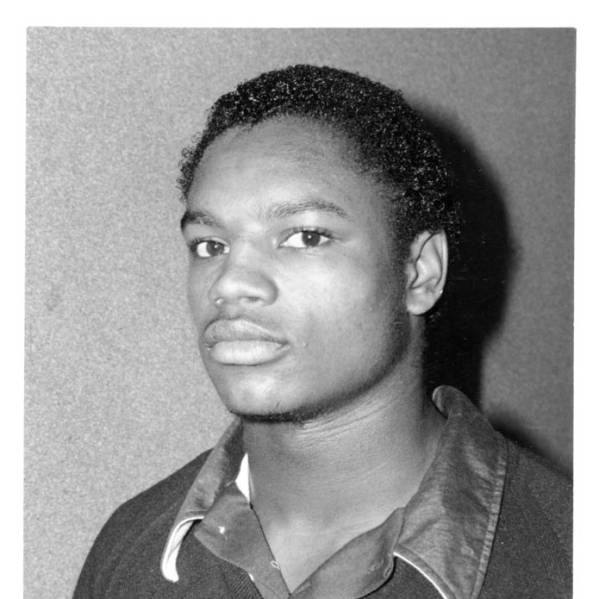

Kevin Willhite, 1981To call his recruiting process “intense” would be a severe understatement. “It seemed like Jackie Sherrill called me every half-hour,” Willhite said. “I’d tell Joe Kapp, ‘No, I don’t want to go to Cal,’ and I’d still see him the next week.” Willhite narrowed the 500 suitors down to four — Notre Dame, SMU, Oregon and Washington. On his visit to Eugene, he saw his name in eight-foot letters on the billboard of an auto dealership near Autzen.

Kevin Willhite, 1981To call his recruiting process “intense” would be a severe understatement. “It seemed like Jackie Sherrill called me every half-hour,” Willhite said. “I’d tell Joe Kapp, ‘No, I don’t want to go to Cal,’ and I’d still see him the next week.” Willhite narrowed the 500 suitors down to four — Notre Dame, SMU, Oregon and Washington. On his visit to Eugene, he saw his name in eight-foot letters on the billboard of an auto dealership near Autzen.

In late January, Willhite announced he’d be playing for Don James at Washington during his recruiting visit to Montlake. “They are going to have a great team next year,” he said. “Everybody’s back and nobody’s on probation and we’ll be on TV — national coverage.” (Oregon was on NCAA probation at the time.)

But a week later, Rich Brooks heard that Willhite was having second thoughts, and assigned assistant Jim Skipper to an exclusive project — prying Willhite loose from Montlake. Skipper was sent to a Sacramento motel room to take advantage of every opportunity to talk to the prize recruit.

He still hadn’t decided on the morning of signing day. UW assistant coach and chief recruiter Al Roberts arrived at Willhite’s home at 6:55am, five minutes before the start of signing day, only to find Skipper in the living room. “What are you doing here?” Roberts asked. Skipper replied, “He never told me no.”

Meanwhile, Willhite was in the bathroom, staring at the man in the mirror. He hadn’t slept all night. But looking in the mirror, he decided he’d be happiest at Oregon, because the coaches had promised he could continue with track. One of the fastest sprinters in his age group, he’d run a 20.81 200 meters, and had a personal goal of making the ‘84 Olympic team and running for his country in the LA Coliseum.

Don James had assured Willhite that “if he could run 10.2 in Eugene, he could run 10.2 in Seattle,” and that UW’s track program was the equal of Oregon’s, a colossal fabrication to which Oregon’s track staff took great exception. Duck assistant track coach Dennis Whitby ensured Willhite’s advisers and family understood the difference between Oregon and Washington in track was roughly equivalent to the difference between the teams in football, in the opposite direction. “I supplied people in Sacramento with the facts… I listed the standing of the two teams in the Pac10 over the last five years, and the scores of the dual meets… and if Kevin still thought they were equal, then so be it.”

And UW was loaded at running back. Jacque Robinson was back for his senior year after being named MVP of the Rose Bowl, and Willhite — if he didn’t redshirt — would find himself no better than third on the depth chart. There were much better prospects for playing time at Oregon, where all the depth was at fullback; at his preferred position of tailback, Willhite would be competing with Harry Billups and Alex Mack, and only Billups had ever carried the ball in a game.

Willhite came out of the bathroom wearing an Oregon hat. Roberts screamed an expletive and insisted on talking to Kevin in private; they spent 10 or 15 minutes in the next room; they came out, Roberts shook Skipper’s hand and left the house.

“Oregon told me I didn’t have to play spring football,” Willhite explained to reporters the next day. Don James had a long-standing policy that all freshmen had to show up for spring ball; no exceptions. Ultimately, this turned the tide in Oregon’s favor, as Brooks told Willhite he didn’t have to participate in any spring football practice if he didn’t want to..

“I have the option of redshirting a year in football at Oregon and training for the Olympics. Washington wouldn’t offer me that… they said I had to play spring ball the first year. I didn’t think, being the top sprinter in the nation right now, that I should have to do that.”

“We’re not expecting miracles from him,” Brooks said on signing day. “He’s a good young back, but how he does and when he does it is up to him… Certainly, he’s the most highly recruited and touted player we’ve ever signed.”

At the first meeting of the Oregon Club in Portland after signing day, 250 excited boosters packed a location set up for 75. Clearly, they weren’t there to talk about Eugene King or E.J. Duffy.

Brooks commenced what would become a five year campaign of dampening expectations.

“People have to give him a break.. When a guy is being compared to Tony Dorsett and Hershel Walker — as Kevin has been — then if he has just a good year as a freshman, people will be disappointed in him…

“We never told Kevin he would be a franchise for us, and I think he appreciated that. We’ve told him we’ve got good running backs, and he’ll have to come in here and earn a spot. But there’s no doubt he’ll have a chance to do that.”

The Injury

After signing with Oregon, Willhite went back to track. Steve Kester, his coach at Rancho Cordova, in an effort to wring as many points out of his star sprinter as possible, worked Kevin to the bone. “I was running 12 races a week sometimes.. [Coach] would say, ‘You have to run, we have a chance to win the track meet.’”

Forced to run multiple events without what Willhite considered sufficient rest, he suffered a severe hammy tear during the Sacramento Metro meet, and either quit the team, or was dismissed, depending on who was asked. His side:

“It was in the 200.. I tried to pop off the turn like I usually do, and it went. I just stopped..

“Coach was so mad, he didn’t even give me any ice. My friends had to go to the store to get it.

“I haven’t talked to him since that day.”

Willhite rested most of the summer. But, in the first 1982 practice, on the first morning of daily doubles, he tried to make a cut and tore some more of the hamstring.

It wasn’t a good start to a career as an anointed star.

“There was a point during the summer when I didn’t even want to come up here… I was hurt and depressed about coming up here and not being myself… [Brooks] told me there wouldn’t be any pressure as far as he was concerned. He said he wanted me to get well.”

The injury was serious; he was instructed not even to jog for months. The ‘83 track season was now in doubt.

On “Picture Day” in August, Brooks asked for everyone to have some perspective.

“How can you expect a lot of someone who can’t practice?

“Kevin’s earned the attention he’s getting, but he hasn’t done anything yet… “

All that attention had, perhaps inevitably, led to some chinks in the armor. The dispute with his track coach - was he a team player? There were allegations that USC had dumped him from the Trojan recruiting list for cause. Recruiting “experts” (yes, they had those in ‘81) were now calling him the “most overrated commodity” of the year. There was his demand to be assigned jersey #1, which was granted, along with subsequent jokes that it really should have been an “I”.

Oregon SID Steve Hellyer heard the noise. “We were taking pictures of all the freshmen and I told them we’d do it in alphabetical order. I half expected him to say, ‘Oh, I’m not sitting through that.’ But he was very patient.. he joked that he was going to change his name to Kevin Alexander.”

The injury? WIllhite was noncommittal. “It all depends on the leg. Maybe I’ll play soon, maybe I’ll play in the fifth game, and maybe I won’t be able to play at all.”

From Seattle, you could probably heard Don James smiling.

Willhite essentially sat out the entire week of daily doubles, only practicing in non-contact drills and at less than full speed. A week later, he was declared out for the 1982 season; that promised football redshirt would come for cause, not convenience, and a year sooner than he’d hoped. “I don’t think anybody should feel sad for me,” he said. “I’ll be 100 percent next year instead of 65 percent this year.”

Brooks said he wasn’t even concerned that Willhite might miss spring practice.

“I don’t want to treat a racehorse like a mule,” he said.

Without Willhite, the Ducks didn’t win a game in 1982 until late November, stumbling through another 2-win season.

Year One

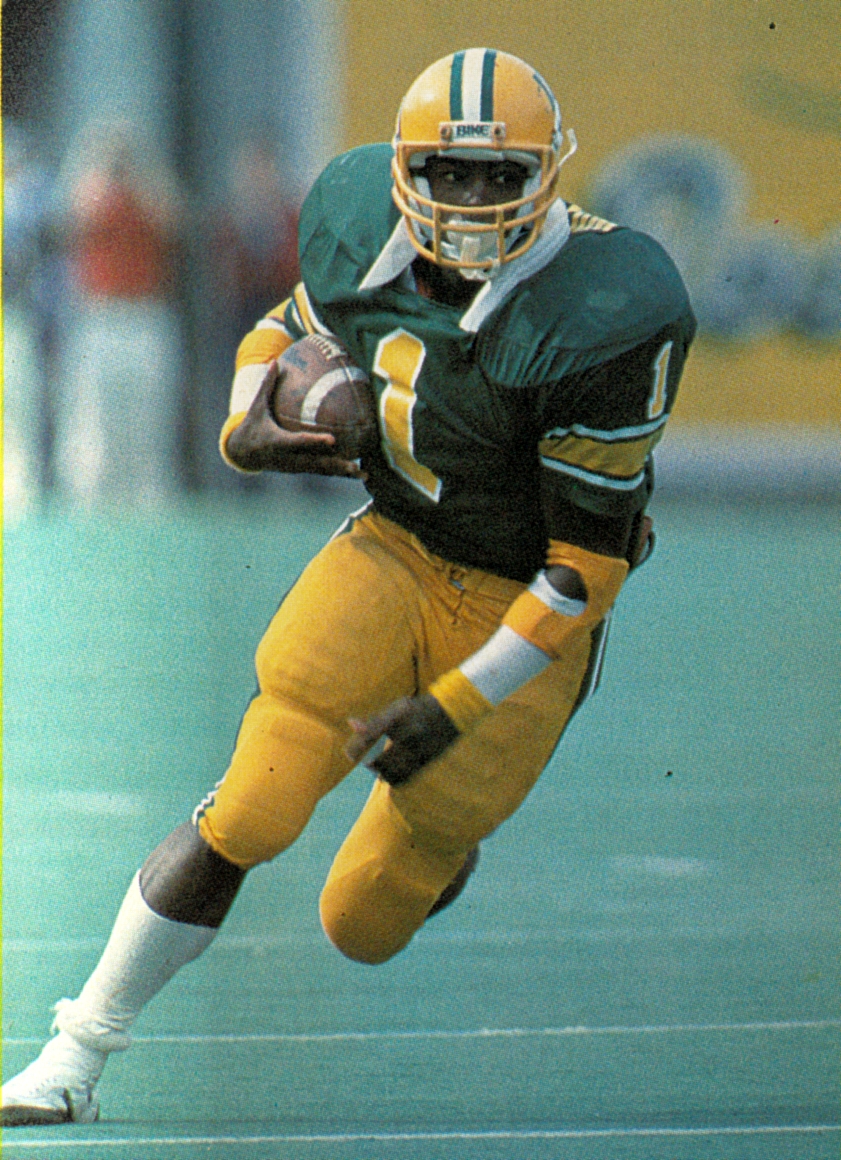

Running the ball in his first fall camp, 1983Willhite sat out the track season and participated in non-contact drills during spring ball. Brooks noted that he was “close to 100%,” but didn’t want to risk damaging Kevin’s confidence by putting him into contact before he was ready.

Running the ball in his first fall camp, 1983Willhite sat out the track season and participated in non-contact drills during spring ball. Brooks noted that he was “close to 100%,” but didn’t want to risk damaging Kevin’s confidence by putting him into contact before he was ready.

Oregon’s 1983 media guide profile didn’t exactly downplay his potential:

“Willhite’s celebrated hamstring was badly damaged and required six months total rest. Needless to say, Kevin was redshirted last fall and should be back to full speed this season.”

Willhite reported for daily doubles in August of ‘83 in what Rich Brooks called “100% healthy condition.” His first touch, in the first scrimmage of camp, after almost two years without contact, went for a 26-yard TD and wowed onlookers. He ended the scrimmage with 49 yards on 7 carries. Showing his versatility, he caught three passes for 53 yards, including a 29-yard TD pass from Chris Miller, where he showed some flair by flipping over freshman CB Ed Hulbert for the score.

Brooks downplayed the effort, only saying Willhite “did very well.” Willhite was less circumspect.

“There’s no doubt in my mind now that I can play and get where I want to be. I know everyone has been doubting me, including the guys on the team and including myself, but I believe I can run and be myself now.”

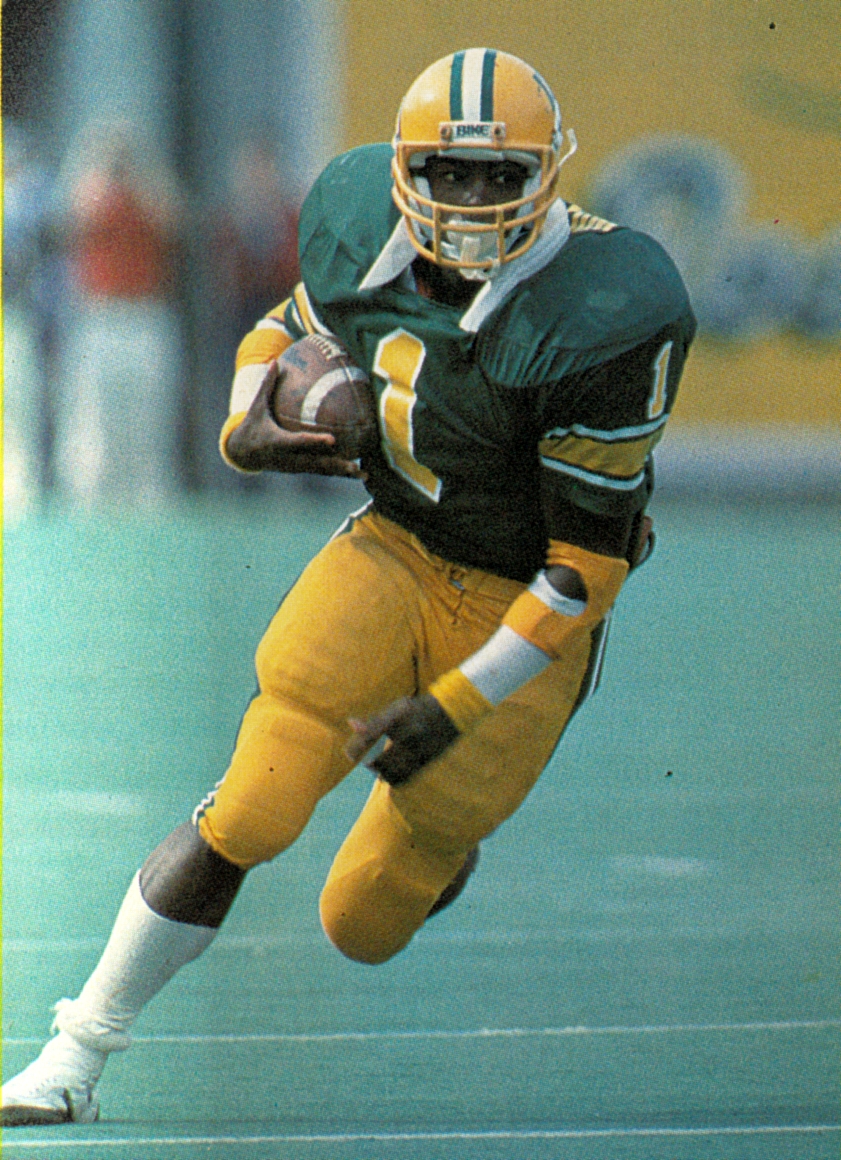

Vs Pacific, 1983In the season opener, at Autzen against Pacific, Willhite didn’t start at tailback, but was in the backfield by the third play. Believers in the eternal power of foreshadowing will not be surprised that he fumbled, at the Duck 32, on his first carry. The Tigers scored three plays later. Oregon lost the game, 21-15. Willhite had carried the ball seven times for 28 yards.

Vs Pacific, 1983In the season opener, at Autzen against Pacific, Willhite didn’t start at tailback, but was in the backfield by the third play. Believers in the eternal power of foreshadowing will not be surprised that he fumbled, at the Duck 32, on his first carry. The Tigers scored three plays later. Oregon lost the game, 21-15. Willhite had carried the ball seven times for 28 yards.

The following Monday, he suffered a badly bruised shoulder in practice. He shook it off, saying he was looking forward to lining up against Ohio State in Columbus. And in an interview, he admitted that in high school, he’d kind of been dogging it.

“I didn’t play anywhere near my potential because I didn’t want to get hurt and lose what I had.. I do not want to be on a high horse and get knocked off again. I will not let that happen. I will not take myself that seriously again. I just tell myself that I’m really not that good.”

By now it was common knowledge that many of his teammates thought Willhite was still dogging it. RG reporter John Conrad wrote: “In a sport where the motto is to play through pain, a lot of the Oregon players undoubtedly had trouble understanding how a hamstring injury could keep a player sidelined an entire year, or how an injured player could get so much attention … During fall camp there was no shortage of people willing to challenge both his ability and his toughness.”

Willhite wanted to prove he was tough. But he knew the process of recovering from the bad hamstring had taken away some of his blazing speed. “Now what I need is to do some speed work. I still believe in my ability.” Unfortunately, speed drills aren’t commonly a focus of mid-season football practices.

Willhite did play in Columbus, gaining 34 yards on 10 carries in a 31-6 loss, and once again fumbled deep in Oregon territory, leading to OSU’s final touchdown.

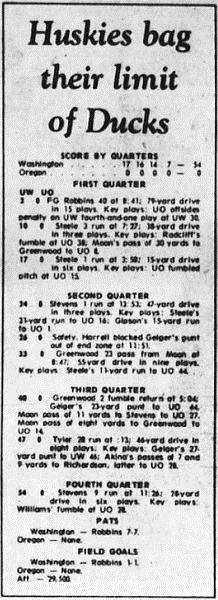

Then, he sprained an ankle in practice during a bye week. He sat out the Houston game, but was back at 2nd string for the loss at San Jose State (12 carries, 35 yards). Willhite finally earned his first start, at home against UW, through attrition, but was no more impressive than the rest of the team in a 32-3 loss. And that’s pretty much how the season went, with Willhite the second-string tailback on one of the more inept offenses in Oregon history (only 152 points for the season and just 283 yards per game).

Willhite told a Sacramento reporter he wished he’d gone to UCLA.

Track Season

Willhite finally got his shot at track in the spring of 1984, after Brooks made good on his promise to release him from spring ball. Oregon track coach Bill Dellinger noted in a pre-season interview that Kevin “needs to lose more weight, but he doesn’t seem afraid of his leg… Realistically, we shouldn’t and I shouldn’t expect too much after being away from the sport almost two years.” He joined fellow running back Harry Billups on the sprint relay, and Dellinger planned to run him in the 100 or 200 as well.

In his first exhibition, a meet in his hometown of Sacramento, he pulled up in the 100 meters, and skipped the rest of the meet. Onlookers noted he didn’t collapse in pain, just kind of slowed down and walked off the track. He told reporters after the meet that he felt a twinge.

Dellinger was not impressed, and told reporters he suspected Willhite wasn’t as threatened by injury as he thought.

“Willhite feeling his leg in the 100 was disappointing… I’m no doctor, but from my experience with people who have pulled muscles, there are going to be twinges as you break loose the adhesions that build up after such an injury… Hopefully he’ll get through that and be able to sprint again. It’s obvious at this point that we don’t have any sprinters.”

And Willhite felt compelled to once again question his coach, calling out Dellinger for putting him in the sprints, saying that running 400s would improve his conditioning and put less strain on his leg. Dellinger fired back:

“He’s run 100s without the leg bothering him. I think there’s a greater chance of him getting hurt right now in the long races because of his lack of conditioning. He’s still about 10 pounds overweight, but he’s making progress.”

In a dual meet against Washington, Willhite stirred the pot some more; the Ducks had a walkover victory in the sprint relay taken away after Willhite was judged to not have given an “honest effort” in a race with no competition. (Washington’s team had been DQd for a false start.) He later finished last in the 200, trailing the UW winner by a full second.

A week later, having failed to convince his Hall of Fame coach that he knew nothing about sprinters, he finished last in the 100 against Cal. Obviously, the speed wasn’t coming back. He was a half-second off his PR in the 100, and almost two full seconds off in the 200. He couldn’t even stand out among Oregon’s extremely weak sprint corps. Dellinger held him out of the sprint relay in the final meet, a triple with Fresno State and OSU; he ran a season-best 10.92 in the 100, good for sixth.

That was it for Willhite’s track career. He didn’t qualify for the Pac-10 championships. The Olympic aspirations, the desire to be a two-sport star, couldn’t survive the injury. “I’ve hung up my spikes unless I think I can get my times down, then I might go out for track again,” he told a reporter.

Year Two

Autumn of 1984. A somewhat humbled redshirt sophomore arrived at fall camp. Rusty from missing spring practice, Kevin was now the fourth-string fullback, just ahead of his little brother Randy, signed by Brooks on Willhite’s recommendation. Brooks told reporters that Willhite “needs to get in shape and have confidence in his leg… He’s down on the depth chart, but I’m sure he’ll be a major factor for us.”

Oregon’s media guide profile of Willhite in 1984 was a howler, a masterpiece of wishful thinking:

Willhite’s first season was excellent by most standards set for freshmen… The only possible disappointment was that Willhite didn’t score a touchdown.

He got that first touchdown in the first game, towards the end of a 28-17 win over Long Beach State. But it was obvious that Brooks had given up any hope of making Willhite a featured part of the offense. Starting tailbacks and QBs got the star treatment in the 80s, not bench-warming blocking backs. And Tony Cherry was the exciting, speedy juco transfer getting all the attention, while Chris Miller worked on his future NFL passing skills.

Willhite carried the ball sporadically in his sophomore season, getting few touches, and not doing much with those. He scored one more touchdown, on a one-yard plunge at Cal, but managed only 15 yards on 9 carries that day.

Brooks had seen enough. Willhite was a DNP (coach’s decision) for the next five games. “He hasn’t shown us the speed he once possessed,” Brooks told reporters before the Washington game. In the middle of the spell on the bench, Willhite, once again, disputed the opinion of his coach:

“I’m not back to full speed, but I have enough to run the football. I can call on it when I need it… When you don’t play in three straight games, it bugs you. But I can’t say I regret coming here. I’ve made my decision and I’ll stick with it.

“I’ll excel in school and other areas.”

He did get the majority of plays at fullback in a win at UCLA, when Alex Mack was injured on the first series, and saw action against ASU and OSU. But, for a player three years earlier hailed as the finest in the country, the lack of production — 27 carries for 111 yards in six games — had to be as frustrating for Willhite as for his fans. His weight had ballooned to 216 pounds from 190 as a freshman; not much of the difference was muscle.

Still, Brooks, ever the loyal master, didn’t give up on his grounded meteor.

“I would hope that Willhite will work hard during the offseason toward getting his speed back. He made progress this year, but there’s still a lot of potential there he hasn’t reached.”

***

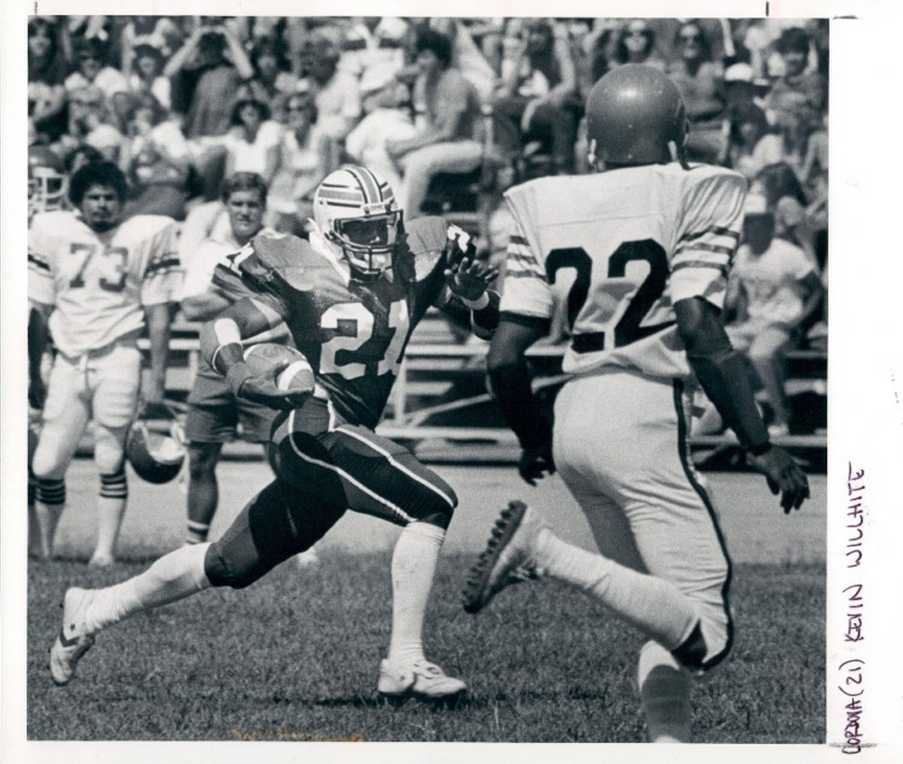

vs Washington, 1985By the spring of 1985, Kevin Willhite was just one of four returning fullbacks on a team with a star quarterback and bowl aspirations. It seemed he understood the importance of showing well in his first full spring camp. And he did, with Brooks pointing out that Kevin had “looked the best he’s ever looked.” He entered fall practice as the #1 fullback, and although it wasn’t a clear-cut choice, “all Willhite needs is better conditioning and he’s ready to be a quality player.

vs Washington, 1985By the spring of 1985, Kevin Willhite was just one of four returning fullbacks on a team with a star quarterback and bowl aspirations. It seemed he understood the importance of showing well in his first full spring camp. And he did, with Brooks pointing out that Kevin had “looked the best he’s ever looked.” He entered fall practice as the #1 fullback, and although it wasn’t a clear-cut choice, “all Willhite needs is better conditioning and he’s ready to be a quality player.

“Kevin is a young man who has been under tremendous pressure since his high school days. People tend to forget that he was 18 years old when he first came here and was holding press conferences for a dozen reporters. I’m not disappointed with Kevin. I know what he’s had to go through.”

Year Three

By now, Oregon’s sports information department was pulling out all the stops to put their disappointments in perspective. Willhite’s media guide entry for his junior season of 1985 was carefully and coyly written.

“Willhite’s obsession to be the player he was billed to be has turned into a desire to be the best he can be. With less pressure to perform, Kevin had the best spring of his career …”

(an interesting way of looking at it, since he’d been no-contact in drills in ‘83, and skipped camp for track in ‘84)

“… and played the best football he has at Oregon regardless of the time of year.”

(Again, one way to look at it, if you ignore that they don’t play actual games during spring camp.)

“Willhite will be hard to dislodge this fall if he improves his conditioning…”

That “conditioning” thing continued to haunt him. While supporting him in public, privately his coaches had been frustrated with Willhite’s attitude; his willingness to train seriously, to get his weight down and improve his fitness level, was being questioned. He’d been skating along, relying too much on his natural talent and quickness. The former couldn’t compensate for the drop-off in the latter after his injuries, but for some reason that message just wouldn’t sink in. But he reported to fall camp at under 200 pounds, and in his best shape since high school. Maybe he’d figured it out at last.

He said things that sounded good to reporters.

“It hasn’t been easy at all. I’ve been up and down the depth chart .. Being sixth string can be pretty tough on you, [but] my career hasn’t been an overall disappointment. I’ve learned a lot. I’ve learned not to depend on my natural ability anymore. And I like the lifestyle in Oregon. It’s not fast and crazy like California.”

— interview with Sacramento Bee, October 1985

But the old ego was still there. Asked about Rueben Mayes and Kerry Porter, the backfield tandem of their opening opponent, WSU, Willhite - along with his starting tailback, Tony Cherry - complained that the Cougar stars were getting all the ink. Maybe, they pleaded, they were being overlooked.

This concept amused WSU coach Jim Walden.

“Hey, their popping off doesn’t worry me. You brag about those that have done it. You people in the press don’t write about guys who haven’t run the length of their nose.”

Considering that Mayes had run for more yards against Oregon in the 1984 game (357) than Willhite had managed in two seasons, Walden had a point. But Cherry had the last laugh; with Willhite blocking for him, Cherry outgained Mayes 143 yards to 81 as Oregon won a 42-39 shootout in Pullman.

Willhite played in every game in 1985, although the numbers again weren’t Heisman caliber. No TDs rushing, under 200 yards on the season, not quite 4 yards per carry. Little brother Randy, behind him on the depth chart, had as many starts as Kevin. But he protected the ball, didn’t fumble, and his blocking helped Tony Cherry become Oregon’s first 1000 yard rusher in 12 seasons.

Still, every time he went on the road, he was the center of attention for reporters. At a mid-season game in Berkeley, he told an interviewer of his frustration at not living up to anyone’s expectations.

“It’s like you were one of the elite people, who was going to become a millionaire, and all of a sudden, you were blown out of the water.”

He admitted to being depressed and gloomy about his situation. But his big brother Gerald had given him a pep talk and helped bring him out of the doldrums.

“I’m going to try to come back to that athlete I was… it’s not in my family to sit back and not fight… I want to show that I can play.”

Year Four

In his senior season, his fifth year in Eugene, Willhite was still fighting the depth chart. But motivated by a desire to follow his big brother Gerald into the NFL, he’d had another excellent spring, worked on his conditioning all summer, and again started the season as the #1 fullback. The ‘86 media guide insisted that “unquestionably, Willhite had his best spring practice since coming to Eugene four years ago.”

By game three, he was back on the bench, behind Alan Jackson.

And before game 7, both Kevin and brother Randy were suspended from the team without explanation.

Kevin returned to the first team a week later against Washington, and started the rest of the way. Brooks singled him out for praise after the Civil War, after he ran for 66 yards and threw some excellent blocks outside for Derek Loville and Latin Berry. “Willhite had probably his best game ever at Oregon… He ran hard and got more chances than usual.

“Kevin’s gone through some difficult times, both personally and physically … If he hadn’t had that ‘greatness’ label coming in… there have been a lot of guys with the greatness label who didn’t turn out so great. He was overrated coming out of high school.

“Kevin’s done the best job that he can do. If he’d come out of high school without the label, people would probably think he’d become a pretty good fullback for our team. Which he has.”

After four years as the center of attention everywhere but on the field, Willhite’s career at Oregon ended without fanfare. There were no encomiums in the media, no special tributes on Senior Day, no post-season accolades. He was just another second-string blocking back who had used up his eligibility.

In his four seasons, he carried the ball 182 times for 731 yards and two touchdowns.

Willhite had never considered the possibility that he wasn’t the best running back in America, like almost everyone was saying, back in 1981. He summed it up in an interview during his senior year:

“I was a pretty good player, who left Sacramento and learned there are other people who are just as good.. Sometimes a setback will help you grow up.

“I should have been a millionaire by now, but I’m not.”

***

Epilogue

Postseason, Willhite was selected for the Japan Bowl, an east-west all-star senior game, and played well. His name wasn’t called in the draft, to little surprise. But the NFL strike that year gave him an opportunity. He signed as a “replacement player” with Green Bay during the scab weeks of ‘87, and in three games ran for 251 yards, including a 61-yard rumble against the Eagles. It was his first time over 100 yards in a game in six years. He dislocated a finger in that game, and the Packers placed him on injured reserve; fortunately for Willhite, that was the last scab game, sparing him the discomfort of playing against defenders who didn’t cross picket lines.

He didn’t survive the Packers training camp the next fall.

**

In the ‘87 Skywriters tour press conference, Rich Brooks closed his session by making an unsolicited observation.

“Wait a minute, I got to get one shot in here. Today is the first time in six years I haven’t had a Kevin Willhite question.”

After pausing for the laughs, Brooks continued.

“I’m here to tell you that Kevin Willhite is a graduate of the University of Oregon and I’m proud of that. He was not a total failure like some writers have said in the past several years.”

Why was he so defensive? Brooks had always resented the way the media had treated Willhite, setting him up as the savior of Oregon Football, then questioning why it wasn’t working out. But there is no question that Brooks himself had fully bought into the hype back in 1981, even discussing how exciting it was going to be to work Kevin’s speed into the offense with two-back sets.

Could a player today be as clearly and wildly overrated as Kevin Willhite had been? Probably not, if the measure of “overratedness” is related to an analysis of talent and potential.

The competition in the Sacramento schools wasn’t sufficient to keep Willhite, who did have talent, from looking like a much better back than he was. In the age of the internets, the level of coverage should make it less likely that a player will be assumed to be good. And the top players now all participate in shoe-company camps and all-star games.

Willhite, in 1981, was never seen outside of his high school team environments. The football world was expected to take his performance on the field at face value, and project it against the next level.

But recruiters and analysts, then and now, find it difficult to measure the intangibles, like a player’s heart and motivation. And of course they have no way of knowing if an injury is going to severely limit a prospect. Another featured back in the 1981 recruiting class, Marcus Dupree, made a tremendous splash during his freshman season at Oklahoma. But there were questions about Dupree’s conditioning and motivation; he clashed with his coach, and didn’t make it through his second year. Dupree is now driving a dump truck for a living in his hometown of Philadelphia, Mississippi.

Kevin Willhite lives in Sacramento, not far from the scene of his greatest triumph as an athlete. He’s Kevin Willhite, 2010 happily married with two children, and works as a supervisor for International Paper. Last fall he was named to the San Joaquin Section Hall of Fame for his high school exploits.

Kevin Willhite, 2010 happily married with two children, and works as a supervisor for International Paper. Last fall he was named to the San Joaquin Section Hall of Fame for his high school exploits.

For all his struggles on and off the field at Oregon, Kevin did take advantage of the life opportunity that his scholarship to Oregon gave him; he graduated, with a degree in rhetoric and speech communications. This put him in the minority of minority athletes, then and now. So, we can’t consider him a failure.

The media, as usual, can be accused of setting Kevin up to knock him down. But they’ll tell you that’s their job. The fans, who were so disappointed that he hadn’t given them more to cheer about, might have considered spending less time buying into the hype in the first place, but can’t be blamed for their initial excitement and subsequent frustration.

There’s your cautionary tale with regards to what a highly touted recruit might bring to your school this fall.

One player doesn’t make a team. Or break it.

Adjust hopes accordingly.

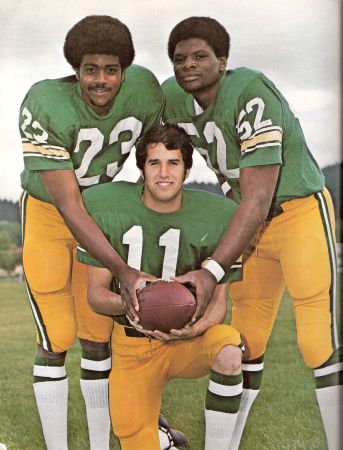

Bobby Moore, Dan Fouts and Tom Graham, 1971

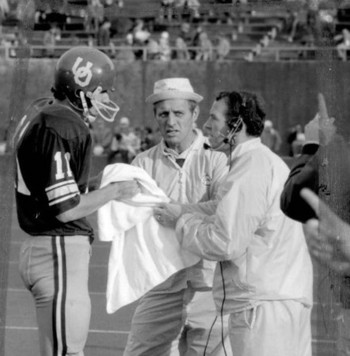

Bobby Moore, Dan Fouts and Tom Graham, 1971 Dan Fouts, Jerry Frei, Bruce Snyder, and a towel, 1971The AstroTurf installed in 1969 had a reputation for being a skating rink in cold and wet conditions. That day, it was very cold, and very wet. Oregon’s turf cleats couldn’t get traction; players lost footing, fumbled, and complained. Fouts blamed the conditions and turf for his performance. He spent much of the game stumbling on his drops, hurrying passes, or being chased by future pro Sherman White, who had some epic battles with Drougas. “That Astro-Turf gets soggy and it lays right down.. They couldn’t get any traction,” Fouts griped. (Of course, Cal was playing on the same field, but as a Bay Area native Fouts probably understood something about wet and cold conditions.)

Dan Fouts, Jerry Frei, Bruce Snyder, and a towel, 1971The AstroTurf installed in 1969 had a reputation for being a skating rink in cold and wet conditions. That day, it was very cold, and very wet. Oregon’s turf cleats couldn’t get traction; players lost footing, fumbled, and complained. Fouts blamed the conditions and turf for his performance. He spent much of the game stumbling on his drops, hurrying passes, or being chased by future pro Sherman White, who had some epic battles with Drougas. “That Astro-Turf gets soggy and it lays right down.. They couldn’t get any traction,” Fouts griped. (Of course, Cal was playing on the same field, but as a Bay Area native Fouts probably understood something about wet and cold conditions.)  Dan Fouts,

Dan Fouts,  Dick Enright,

Dick Enright,  Jerry Frei,

Jerry Frei,  Norv Ritchey in

Norv Ritchey in  Suffering

Suffering