In honor of African American History Month, this post, and today’s entry in The Program Project, is dedicated to a man listed in the program, who was not allowed to play in the game.

In honor of African American History Month, this post, and today’s entry in The Program Project, is dedicated to a man listed in the program, who was not allowed to play in the game.

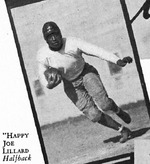

There he is, on page three of the 1931 USC program. “Happy” Joe Lillard, he’s tagged. He’s listed on the roster, there’s a posed action shot, but when game time rolled around he wasn’t on the field.

The short version: Lillard, a halfback recruited by Oregon head coach Doc Spears at Minnesota who followed Spears to Oregon in 1930, had been declared ineligible by the Pacific Coast Conference earlier in the week. He had been accused of playing semi-pro baseball, in violation of conference regulations.

Without his star player, Doc’s team had about as much chance of success against Howard Jones’ eventual national championship USC team as Joe Lillard had of making it as a black player in the white football world of the Thirties.

The pre-war color barrier of college football

In pre-WWII White America, the Black college football player had his place; that place was in the “traditional Negro colleges of America.” The notion of separate-but-equal-wink-wink was firmly entrenched in the college sports culture. Black athletes laced up their cleats in the “traditional white colleges of America” at their peril. (Iowa State’s Jack Trice Stadium is named for the player who broke ISU’s color barrier, in 1923, and was brutally stomped by Minnesota’s players in his first and only game; hospitalized for lung hemorrhage and internal bleeding, he died two days later.)

Lillard hadn’t broken Oregon’s color barrier. That task had fallen to predecessors Bobby Robinson and Charles Williams, who played under Cap McEwan from 1926-1929. In fact, Joe was just one of several outstanding players Doc Spears had brought along when he arrived in 1930. Many of the Spears recruits would wind up starring for other teams. Bill Bevans and Stan Kostka wound up All-Americans back at Minnesota; Tuffy Leemans transferred to George Washington after his freshman year, and wound up in the NFL Hall of Fame.

But the story in 1931 was of “Happy Joe.” How a black orphan from Iowa wound up playing football for a team in a lily-white community with a MD for a head coach. How they’d given him a chance, and then taken it from him.

For years afterwards, the talk in Eugene was of what might have been with Lillard. The hype surrounding his arrival in Eugene was the 1930s equivalent of DeAnthony Thomas becoming a Duck in 2011. The Thomas comparison is apt, as Lillard was considered by some in 1931 to be the fastest man who had ever played college football. Ever.

Growing up

Joe Lillard was born in Mason City, Iowa, described in a SI profile as “a rough-edged boomtown of immigrants and a welter of prostitution, drugs, bootlegging and ethnic violence.” His father, Joe Sr., a coal miner, had left home when Joe was a toddler. His mother died when he was nine. Joe and his sister Julia were taken in by a family friend for a time, but eventually he was sent to a boarding and trade school in Eldora, Iowa. It wasn’t a juvenile home; there were no fences, and Joe became a “civil engineer,” helping take care of the big boiler that heated the campus.

Joe Lillard was born in Mason City, Iowa, described in a SI profile as “a rough-edged boomtown of immigrants and a welter of prostitution, drugs, bootlegging and ethnic violence.” His father, Joe Sr., a coal miner, had left home when Joe was a toddler. His mother died when he was nine. Joe and his sister Julia were taken in by a family friend for a time, but eventually he was sent to a boarding and trade school in Eldora, Iowa. It wasn’t a juvenile home; there were no fences, and Joe became a “civil engineer,” helping take care of the big boiler that heated the campus.

The school had a football team. Joe started on the varsity for his last two seasons there; he also played basketball, baseball, and track. At 14, he was a good sized lad and was often mistaken as much older. He left Eudora when he was 15, returning to Mason City, where he graduated from grammar school. At Mason City High, Joe made the All-State football team during his sophomore year, was All-State in basketball for three years, and – because the high school didn’t have a team – pitched for a city league team that won its championship.

Joe graduated from Mason City High in 1927. He was twenty years old, six feet tall and weighed 185 pounds, and built like Jim Thorpe. He married his high school sweetheart. He had planned to enroll at the University of Iowa, but didn’t have enough money, so he went to work, as a chauffeur and dance instructor. In 1928 he got a job driving for a barnstorming baseball team; in the winter, he played guard for the Savoy Big Five, the predecessors of the Harlem Globetrotters.

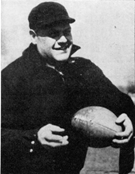

Later that year, he tried to enroll at Minnesota. Lillard had admired its coach, Clarence “Doc” Spears, but had heard Spears was opposed to using black players. So Lillard went to Spears and asked him about it; Doc assured him he had nothing whatsoever against black athletes, and that all players would get the same consideration for playing time. Thus convinced, Lillard decided to enroll at  Clarence “Doc” SpearsMinnesota, only to find his high school credits were inadequate.

Clarence “Doc” SpearsMinnesota, only to find his high school credits were inadequate.

Then, in 1930, after spending the summer working as a driver and playing part-time for a semi-pro team in Jamestown, North Dakota, Joe caught a break. He knew Spears had moved on to coach at Oregon. The Webfoots were playing Drake University in Chicago; Joe went to the game and arranged an interview with the coach. By then, he’d saved enough money from working and playing semi-pro baseball to get to Oregon, and resolved his high school credit issues. Spears assured him that boosters would help him find a job.

And so, Joe Lillard came to Oregon, in October of 1930, right in the middle of freshman football camp.

Welcome to Oregon

Johnny Kitzmiller was wowing the crowds on the Coast with his running and passing, but all anyone seemed to want to talk about was this new “boy” on the Frosh:

“Oregon seems to have found another Kitzmiller in Joe Lillard, colored boy from Minnesota. A versatile boy, he passes, carries and kicks the ball like a veteran… The best part about Lillard is that his usefulness will not terminate with the football season, for he also plays basketball and baseball, and is quite a hand at various track activities.”

– Roy Craft, Eugene Guard, 25 Oct 1930

From the UO Frosh - OSC Rooks game, won 7-6 by OSC, story by Vincent Gates of the Guard:

“Phantom shades of Bobby Robinson flashed across the gridiron of Bell Field, Corvallis, last night, as Joe Lillard, twisting, dodging, hard hitting colored streak from Prink Callison’s freshman team made his debut in college football for Oregon … Callison’s green-shirted huskies lost a thrilling penalty-marred game as some 5000 frenzied spectators watched Lillard break away time after time from the Staters babes, throw passes with the accuracy of Kitzmiller and run back punts like Red Grange, only to be removed from the game in the closing quarter after he had run 52 yards through a broken field for a touchdown to virtually tie the score, and then went over again in the last canto after returning a punt 60 yards through the entire rook team. But Joe’s determined efforts were in vain, for … Oregon’s yearlings were offside when the last play started.

“The score wasn’t written in digits… rather, in the fleet feet and the white heart of Joe Lillard, who because he was black, was smothered again and again, jumped on, kneed and knocked out, but who wouldn’t leave the game, even after he was deliberately flattened unconscious from an obvious roughing tactic of an over enthusiastic rook… The rook was sent home and his teammates were penalized half the distance to the goal line, some 65 yards away.

“Joe recovered, came back fighting, and took another punt back to almost its original send-off and then went out, unwillingly.”

A couple of weeks later, Lillard was referred to in the Guard as “‘Smiling Joe’ Lillard, God’s colored gift to Oregon,” after leading the Frosh to a win over Washington.

So, Lillard’s debut with the varsity in 1931 was highly anticipated. Oregonian sports editor L.H. Gregory wrote after one fall practice:

“Doc was not very happy. And then, presently the scrimmaging started, and on the third or fourth play one team punted and Happy Joe Lillard, the colored boy from last year’s freshman team they’re talking about on every campus on the coast, reached out and grabbed it the way an outfielder takes a fly.

“Happy Joe tucked the ball under his arm, made a feint in one direction that left a would-be tackler sprawling in the sawdust, and suddenly shifted his hips at a 45 degree angle the other way whereupon two more tacklers missed him. Another lightning change of direction, another shift of the hips without slackening of speed, as other tacklers sprawled by the wayside, and the Midnight Express was on his way.

“All Happy Joe did with that punt was to run through the entire team for a touchdown. Incidentally, it was his second afternoon in a uniform.

“Doc Spears brightened a little. He almost smiled.

“A couple of minutes later, Joe’s side took the ball. Lillard on the first play got through tackle for 30 yards … on this dash seemed to be running with his legs permanently angled out sideways at 45 degrees.

“Something like a smile flitted across Doc’s lips.

“Then Joe’s side called a pass. Happy Joe took the ball and began running full speed, as if on an end run, but instead he shot the ball as a second baseman would throw on the run to first, and it went 20 yards like a shot squarely into the arms of the receiver. He dropped the ball, but the way Joe had put it just where he wanted, with perfect timing, caused Doc to give something like a short laugh.

“Half an hour later when Happy Joe shuffled smiling off the field, Doc Spears was a different looking football coach.”

— L.H. Gregory, Morning Oregonian

The “Gentlemen’s Agreement”

Spears kept Lillard on the bench during early season non-conference warm-ups against Monmouth and Willamette. His first varsity action, against Idaho in Portland, saw him double- and triple-covered every time he came near the ball. Spears sat the frustrated Lillard to calm him down. In the 4th quarter, with Oregon holding a tenuous 2-0 lead, Lillard went back in. On his first play, he ran around end for 23 yards, knocked out on the Idaho 8. On the next play he swept the other end, the blocking was perfect and he had his first varsity touchdown; after one more carry, for 15 yards, Spears put him back under wraps for the big game in Seattle the following week.

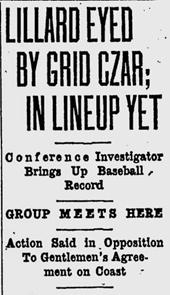

But it had only taken one game for Lillard’s play to prompt an investigation into his legitimacy as a college athlete.

All hell broke loose on Thursday, the 8th of October. Jonathan Butler, the first commissioner of the Pacific Athletic Conference, had slipped into town unobtrusively and informed Oregon’s faculty athletic representative, H.C. Howe, that Butler had proof Lillard had played for the Gilkerson Colored Giants, a “Negro barnstorming team.” It was Butler’s first reported act as commissioner. Professor Howe, on being informed that Lillard was ineligible, declared him out for the Washington game. Later that day, the faculty committee, recognizing that no formal complaint had been filed, reinstated his eligibility on a temporary basis.

All hell broke loose on Thursday, the 8th of October. Jonathan Butler, the first commissioner of the Pacific Athletic Conference, had slipped into town unobtrusively and informed Oregon’s faculty athletic representative, H.C. Howe, that Butler had proof Lillard had played for the Gilkerson Colored Giants, a “Negro barnstorming team.” It was Butler’s first reported act as commissioner. Professor Howe, on being informed that Lillard was ineligible, declared him out for the Washington game. Later that day, the faculty committee, recognizing that no formal complaint had been filed, reinstated his eligibility on a temporary basis.

The perception was that Butler had stuck his nose well into an area that he had not been expected to be sniffing around. A clearly incensed Spears told reporters the new commissioner had been hired a month earlier to “make a year-long study of athletic conditions in the PCC, and file a report with conference officials when he was finished.

“Instead, he comes into Eugene with a lot of information and singles out Lillard … There are a lot of other players in the conference who have played semi-pro baseball. Why not wait until he has information on them and then throw the whole bunch out at once?”

The problem was that the “charges” were true. There had been no cover-up. A “gentlemen’s agreement” among the colleges allowed athletes to play semi-pro ball, work jobs during the summer, and find various other ways to be compensated for their time away from the team.

And Lillard readily admitted to having been compensated for playing semi-pro ball, in Minnesota and North Dakota.

But the “gentlemen’s agreement” did not apply to black players. The rule was unwritten. So was the exception.

“It … will be highly enlightening news to a lot of the lads in this conference that playing semi-pro baseball in summer henceforth is to be regarded as an eligibility crime.. In the ‘Big Ten’, where Mr Butler comes from, it’s quite an offense. They have rather high-minded beliefs back there. It horrifies ‘em to think a young fellow might soil his hands with summer money … But for years on the coast, there has been a gentlemen’s agreement, that if an athlete did not sign with a club in organized baseball, what he did in semi-pro circles was not particularly the conference’s business. You will not find this agreement in the conference rules. Nevertheless everybody in the conference knows about [it]…

“Somebody sent Mr Commissioner-Elect butler to Minneapolis to root around for what he could find. Whom do you suppose?

“… In just what respect is a little semi-pro baseball in summer so much more damnable to the salvation of a football player’s eternal soul than holding down a $125 to $250 a month “job” – such “jobs” exist, you know – at some of the larger institutions of this same coast conference?”

– L.H. Gregory, Oregonian

Butler, for his part, seemed to have been acting as a self-actuated defender of amateurism. No team admitted filing any form of protest or complaint; quite the opposite – they all went on the record denying having anything to do with the protest. Idaho’s coach said his school wouldn’t protest the Oregon game; USC’s athletic director denied any involvement in a protest or complaint. But USC’s athletic director had made the first inquiry to Oregon regarding Lillard’s baseball play, and it’s not a stretch to assume this inquiry put the case on Butler’s radar.

And Washington coach Jimmy Phelan said that despite the upcoming game, his school had had nothing to do with the eligibility protests. “We’ve built our entire defense toward stopping Lillard,” he said. “I am glad he’s going to be in there.”

Joe’s Last Game

Phelan’s strategy was ineffective. The Webfoots logged a 13-0 upset of the Huskies. Spears took advantage of the obsession with Lillard, not starting him, and using him as a decoy numerous times. Joe let his mark on the game anyway; two drive-killing interceptions, two coffin-corner punts of over 65 yards, and a rushing TD. But the hero of the Washington game was Bill Bowerman, whose 87 yard interception return for a TD in the 4th quarter broke the game open.

Joe Lillard didn’t know he had played his last conference game. He prepared with the team for the train ride to Los Angeles and a date with the mighty Trojans, who were well aware of his abilities:

“… Smoky Joe is rated the greatest one-man riot wearing grid armor in the great Northwest … the alpha and omega of the University of Oregon eleven. Whatever hopes the Webfeet have of going places in the Coast Conference race rest squarely on the shoulders of the stalwart Negro boy who has received more publicity than any other northern grid athlete… He combines shiftiness with his ability to radiate rapiditiy. Smoky Joe is also an exceptionally fine passer.”

— Braven Dyer, Los Angeles Times 11 October 1931

A few days later, the PCC faculty representatives met at Portland’s Multnomah Hotel for what was described as a “raging five-hour debate.” Professor W.B. Owen, from Stanford, the faculty board chairman, was able to push through his demand that the “gentlemen’s agreement” be abolished, and that playing semi-pro baseball would result in forfeiture of collegiate eligibility. There were concerns that if Lillard wasn’t declared ineligible for his summertime diamond work, that other, uglier charges would be used against him.

The Oregon supporters around the table — essentially the northern “division” of the conference, whose players didn’t have the job opportunities available in California, and often played semi-pro ball to help make ends meet — caved. “Happy Joe,” “Smiling Joe,” “Shufflin’ Joe”, the Midnight Express, Joe Lillard was declared officially impure and stripped of his collegiate credentials, for the crime of playing semi-pro baseball under an “assumed name.”

The absurdity of the charge is breathtaking. Lillard had admitted playing semi-pro baseball under his own name. What possible advantage with regards to eligibility could he have gained by also playing under someone else’s? And the “assumed name?”

It was Johnson – his half-brother’s name. According to Roy Craft of the Guard:

“Joe’s brother, Ben Johnson, was well known as a baseball player in Jamestown, ND. Naturally, Ben’s little brother was welcomed on the team, and though some knew that Joe was a Lillard and not a Johnson, he was generally known as Ben’s brother, and the Johnson moniker came as a matter of course. Lillard could probably have spiked the misnomer easily enough, but he carelessly allowed the name to persist, basking no doubt in the reflected popularity.”

— Roy Craft, Eugene Guard

The “assumed name” was the official charge. Unwritten into the documentation of the eligibility ruling was Butler’s declaration that Lillard was an “ex-reform-school tough and a rowdy.” There had been complaints from OSC’s freshmen that it was Lillard himself who had instigated the fight that had left him bloodied and sore. From there, it didn’t take much to turn that Iowa boarding farm orphanage into a juvenile delinquent’s reform school. And the conference couldn’t have that kind of player polluting their teams.

Amateurism’s Ironies

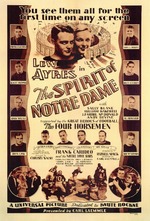

While all this was taking place, a big hit in the theatres was “The Spirit of Notre Dame,” a movie in which some 40 USC players appeared, playing football. Each earned $10 a day. Since this was “movie work,” and not semi-pro baseball, the Trojan eligibility was never in question. USC was at full strength for their game against the Webfoots. Oregon’s players were crestfallen over the unjust loss of their teammate, and they were hammered by the eventual national champions, 53-0.

While all this was taking place, a big hit in the theatres was “The Spirit of Notre Dame,” a movie in which some 40 USC players appeared, playing football. Each earned $10 a day. Since this was “movie work,” and not semi-pro baseball, the Trojan eligibility was never in question. USC was at full strength for their game against the Webfoots. Oregon’s players were crestfallen over the unjust loss of their teammate, and they were hammered by the eventual national champions, 53-0.

Many observers of the time felt it was this loss – and the loss of Joe Lillard – that caused Doc Spears to re-evaulate his tenure at Oregon. Indeed, his career in Eugene, that had started out with such promise, 11 wins in his first 13 games, faded quickly after the Lillard debacle. Without Lillard, there was no offensive threat, and the 1931 Webfoots were shut out four times in their last six games.

By 1932, Spears was back in the Big Ten, at Wisconsin. His two year record at Oregon (13-4-2) stood as the best career-opening record at Oregon until Chip Kelly surpassed it in 2009-10.

It’s been speculated that the real reason Lillard didn’t go to Minnesota to play for Spears was the same issue that cost him his eligibility at Oregon — his semi-pro baseball record. The Big Ten schools were said to have had a higher standard of “amateurism,” and in fact Jonathan Butler had learned his investigatory trade at the Big Ten before going to the PCC. During that visit in Chicago, at the Drake game, had Spears told Lillard of the PCC’s “gentlemen’s agreement” — and that, unlike at Minnesota, he’d be able to play college sports without regard to his financial history? It’s a reasonable supposition, albeit one that assumes a certain naivete, or at best optimism, on the part of Spears.

Epilogue

His collegiate options eliminated, Joe Lillard went to the NFL. He starred for the Chicago Cardinals, but his career was cut short by another “gentlemen’s agreement” — among the NFL owners, to bar all African American players after 1933. Lillard and Ray Kemp, of Pittsburgh, were the last black players in the NFL until after World War II. The Cardinals justified cutting Lillard because he had earned a reputation as a fighter, which was probably true; if you’re at the bottom of a pile of players who all want to kill you because of your skin color, wouldn’t you fight back? Just like you had to do back in 1930, on that field in Corvallis?

“A rival player would provoke Lillard, and Lillard would fight back. At a time when black athletes were expected to perform the act of stoicism known as “taking it,” Lillard’s retaliations were regarded by all whites and many blacks as prideful foolishness, if not sheer lunacy. “An angry young man” is how fellow black NFL player Ray Kemp remembered Lillard. By November of his first year with the Cardinals, Lillard’s teammates had stopped blocking for him. Chicago Defender columnist Al Monroe pleaded with him to “learn to play upon the vanity” of whites. “He is the lone link in a place we are holding on to by a very weak string.”

“But Lillard did not listen: In his second NFL season he was thrown out of a game against Pittsburgh. Two weeks later he punctuated his game-winning field goal with a retaliatory uppercut to the chin of Cincinnati Reds guard Lester Caywood—who had punched him just after the kick—causing a near riot. By the time the string finally snapped, Lillard had evolved into a segregationist’s fondest dream: living proof that whites and blacks should not mix.”

— Daniel Coyle, “Invisible Men”, Sports Illustrated 15 Dec 2003

Barred from the NFL, Lillard remained a football player for several more years, competing in minor leagues in Harlem. He eventually settled in Queens, working at an appliance store and in sporting goods. Lillard died in New York City’s Bellevue Hospital Center on September 18, 1978, of complications from a stroke.

***