Bill Byrne had a dream. He wanted to cover Autzen Stadium with the world’s largest A-cup.

The big-idea Oregon athletic director (1984-1992), who took Oregon football from also-ran to bowl status during his tenure, didn’t like to let practical matters obscure the big picture.

In the spring of 1985, Byrne began an all-out push for a dome over Autzen. The 820-foot covering would, Byrne felt, help keep Oregon football viable in an increasingly competitive Pac-10 environment.

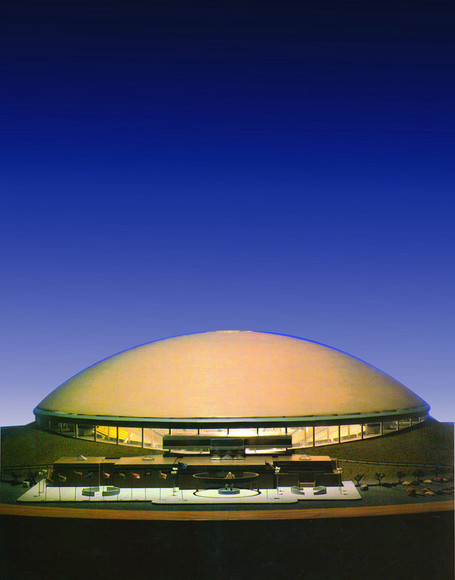

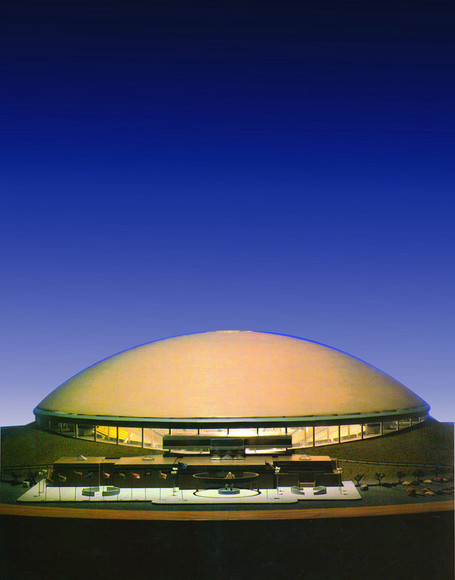

Model of the proposed Autzen Dome, 1986; west elevation. Made by Scale Model Co of Cottage Grove. Source: 1986 Oregon Football Media Guide, back cover

Model of the proposed Autzen Dome, 1986; west elevation. Made by Scale Model Co of Cottage Grove. Source: 1986 Oregon Football Media Guide, back cover

Oregon’s football fortunes in the mid-1980s were, to put it bluntly, limited. The 1984 team, despite a 4-0 start and a winning record, hosted the lowest average attendance in the conference, under 26,000 fans per game. Attendance that year was literally dampened by wet weather for three of the six home games. Byrne figured the semi-rain-outs had cost the school $250,000 in revenue from tickets and concessions alone, with losses to the overall economy from depressed game day traffic well beyond that.

There was pressure on Oregon’s conference status from the “haves” of the Pac-10. In 1984, USC officials proposed to double the conference’s football guarantee to visiting teams, to $150k per game, a proposal that would have broken the bank at Oregon (and OSU and WSU), likely driving them out of the Pac-10. The proposal failed that time, but the point was made: Put up, or go play with teams your own size.

18 year old Autzen Stadium itself was a bit of a dump. The locker rooms and meeting facilities — designed in an era of one-platoon football, and never expanded — were lousy, although the Stadium Club, completed in 1981 at the east rim, had at least given the coaches somewhere to hold meetings besides the 50 yard line. The athletic offices themselves were a 10 minute drive away, at Mac Court. And, from the fan’s perspective, Autzen’s legendary Honey Bucket Brigade around the rim, and the occasional plumbing failure of the few permanent fixtures, located in unheated concrete boxes, spoke volumes about those other facilities.

Enter the dome concept. Cover the stadium, put a ring of skyboxes around the rim; sell the skyboxes to corporations, who could take fat tax deductions for their largesse. Sell future recruits on the opportunity to play and practice in a warm, dry facility. And during the offseason, turn Autzen into.. well, the world’s weirdest convention center, I guess, but that was the idea.

Moreover, there was talk that Mac Court itself couldn’t last forever. A domed stadium could be “draped off” for basketball — ala the Carrier Dome at Syracuse — and the resulting arena, with portable seating, could comfortably fit 17,000 for hoops. The increased capacity alone, Byrne felt, could potentially raise another half million dollars per year in revenue, assuming there were 17,000 fans willing to watch Oregon basketball in person (a dodgy assumption then as now, but I digress).

Byrne’s predecessor, Rick Bay, had come up with the original concept. Beyond floating the idea and failing to get a large corporate donor to put up most of the cash, he didn’t do much with it. When Bay left for Ohio State, the dome project was on Byrne’s desk, and he loved it.

Byrne’s big problem with his big dream was the same as Bay’s; as is usual with dreamers, how he’d pay for it.

The initial plan — a total project estimated at $15 million — called for funding by a combination of in-kind gifts, contributions, and — in a move that was ahead of its time — the sale of permanent seat licenses for basketball and football.

Ultimately, none of this worked out. And it’s a good thing it didn’t. It’s hard to look at Autzen now and imagine it sporting a 20-year-old dust cover. A permanent dome would have likely made the 2002 seating expansion impossible. But, back in the day, the concept was taken very seriously by a lot of people.

The timeline:

April ‘85 — Byrne gets UO approval to start feasibility studies on the project. He immediately hits the PR trail; the local media eats it up. “I’ve got to pull this off”, he says in a R-G interview. “I’m absolutely convinced we’ve got to have it.. I don’t want to give anybody the idea this is all set, but I do believe we won’t continue to be a viable member of the Pac-10 if we don’t do it.”

Duck football coach Rich Brooks, for his part, likes the idea. “In recruiting, you get the talk all the time from the [southern schools], ‘Why do you want to go up there where it rains all the time?’”

Byrne figures a total of $7.5 million in donations and gifts-in-kind will be required to start the project. No mention at the time was made of state funding, but privately, nobody really thinks the dome will happen without some public financing, in the form of bond issues or lottery cash. There is no billionaire shoe magnate sugar daddy with enough cash and ego to support the project alone.

May ‘85 — The sides are chosen up, with the local business community generally coming down in favor of the project as an economic boon, and the university’s faculty and Eugene’s liberal elite generally wailing against it as an economic catastrophe in waiting, unfair to the long-suffering professors of underfunded departments, and as usual, “What about the children!?”. Most questions about the project from supporters concern the feasibility of funding in an economic down cycle, whether attendance could be more predictably improved by fielding a better football team, and why anyone would want to play basketball in a football stadium with drapes at the 40 yard line.

The responsibility for greenlighting the project itself falls on Oregon President Paul Olum, not known as a big football guy, with his radical conception of a university as an educational facility. Olum was on the record as not wanting a fundraising campaign for a dome to get in the way of a major late-80s capital campaign for the university as a whole. But Byrne was optimistic; he thought that if all the approvals and fund-raising went smoothly, the project could be completed by 1990.

Sept ‘85 — So much for all that private financing: The U of O Foundation proposes to the Lane County Commissioners that they permit use of state industrial revenue bonds to finance the dome, a concept that would lead to lower-cost financing than a standard taxpayer-financed bond issue. It was up to Byrne and the Foundation to show the project is cost-effective.

Although the promised feasibility studies are not complete, Oregon VP Dan Williams insists that they aren’t going to start building as soon as approval was granted; they just want the approvals first. And the rules of the game stated that the county had to okay any proposal before it would be brought to the state board.

What was the hurry? There were indications that Congress, in consideration of a huge tax reform bill, could eliminate the very types of financing that would be required to build the project. Get it done now, and hope that the project could be “grandfathered” under the old tax rules.

The county commission approved the application in October on a 3-2 vote.

Oct ‘85 — Byrne goes to OSU AD Lynn Snyder for approval to play Oregon home games in Corvallis in ‘86 or ‘87, in the event that dome construction makes Autzen unusable. Although this, in retrospect, was the single best reason to forget the project altogether, Snyder, in effect, says “Sure, might as well have one mediocre team playing here,” and proposed not even charging Byrne rent.

Following the county bond OK, the Oregon Economic Development Commission declared the not-yet-feasible project eligible for up to $20 million in state industrial bond funding. The prospect of dry football fans did not win over the commission; rather, it was the projected economic boon that a domed stadium would allegedly provide the area.

Former Eugene Mayor Gus Keller, a member of the state EDC, said “The presentation was so comprehensive it was frightening.”

Equally frightening is the ‘85 Oregon football team, which loses at Nebraska 63-0, and winds up 5-6, not beating a team with a winning record. Still, attendance is up by over 9,000 per game from ‘84, a difference that can’t totally be pinned to better weather (one wet game, and a sub-freezing Civil War).

The Oregonian blasts using industrial revenue bonds to fund the project as an “abuse of the concept.”

Dec ‘85 — Proposals for the dome’s architecture are entertained by Byrne and other officials. The original “All Wood Because This Is Oregon And We Got Wood” plan still has Byrne’s support, but for variety, his team looks at proposals for an inflatable fabric dome and a steel dome designed in Europe. The first legitimate estimates for the dome portion of the project come in at $9.75 million. Byrne’s guesstimate in April is 30% short of reality.

Byrne professes to be unconcerned about the tax reform bill, convinced that the project’s funding would be grandfathered in. And he is even more adamant that dome construction is absolutely essential to Oregon’s future in the Pac-10: “We don’t have a choice.”

Jan ‘86 — When Paul Olum gives the thumbs-up on January 22 after meeting with Byrne, the project is as close to reality as it ever gets. Olum’s approval is essentially a “go ahead, knock yerself out”, conditional upon Byrne’s ability to raise:

— $9 million from the sale of 6,000 personal seat licenses at $1500 each; and

— an unspecified amount in donations and gifts-in-kind from major donors (presumably making up the difference in cost between the other guarantee items and the project cost).

Olum, wisely, places the university administration in a can’t-lose situation. Not caring all that much about football, he puts himself in the position of not sticking his neck out. By not begging for public financing or reassigning critical university resources, he put the whole project on Byrne. And he is able to deflect cries from professors about misplaced priorities by pointing out that none of THIS money was likely to be donated for a new roof at the library.

It is now Bill Byrne’s project, sink or swim.

Feb ‘86 — A documentation error found in the state EDC revenue bond application forces a review of the EDC’s approval of the project. The U of O Foundation, when preparing the application, stated concession revenues as concession profits, overstating the increased income from the dome improvements by about $400,000 annually. Oops! The EDC would readdress the application in their March meeting, delaying any fundraising activity by a month.

Oregon House Speaker Vera Katz, in a letter to the president of the State Board of Higher Education, suggests the financing method itself is “a convenient legal fiction for escaping carefully crafted and necessary controls over public indebtedness.” One troubling aspect is the plan to transfer title to Autzen Stadium to the U of O Foundation from the university, a possibly illegal transfer of state property to private (albeit non-profit) hands.

Meanwhile, Pac-10 representatives vote to raise the traveling-team guarantee to $125K per game, up from $75k.

Oregon signs a good recruiting class, with players like Terry Obee and Derek Loville enticed by promises of a domed playing field.

March ‘86 — The former general manager of a Portland potato chip company forms a committee to bring the 1996 Winter Olympics to Oregon. Seriously. The opening and closing ceremonies, ice hockey and figure skating will be held in the covered, and presumably ice-rink-equipped, Autzen Stadium. Plans to hold ski jumping competition on Spencer Butte never get off the ground.

April ‘86 — On further review, based on a legal opinion by UO counsel, the plan to transfer Autzen ownership to the UO Foundation is scuttled.. and along with it the idea of using the state industrial revenue bonds. VP Williams tells reporters that the university is looking into “more traditional financing” (in other words, ordinary taxpayer-guaranteed bonds).

Perhaps not coincidentally, as of early April, the university has still not hired a financial advisor for the project.

The skybox designs are scaled back; all skyboxes will seat 20 fans each, and lease for $25k annually on a ten-year lease.

May 86 — Thanks in part to the increased football road-trip guarantee, Byrne announces severe budgetary shortfalls at the athletic department. He plans to drop swimming and women’s gymnastics altogether, sports not expected to draw bids for personal seat licenses at the dome, and cut staffing. Byrne stresses that the budget deficit closed by the cutbacks won’t affect the dome project, and only “non-revenue-producing” sports would be affected by cutbacks (nudge nudge wink wink). Supporters of Oregon track and field cry foul at proposed draconian slashing of 16% of the track budget. Craftily, the track folks don’t mention the upcoming Hayward Field renovation project, which would almost certainly siphon some dollars in donations away from the dome.

The Register-Guard polls its readers on the cutbacks, the dome, and athletics in general. Among the thoughtful comments received: “I will not pay $3, or whatever, to park my car. That is the biggest ripoff of all time and you won’t see me at any more games until the parking is free.”

August 86 — After a summer of fundraising, Byrne announces on the eve of the ‘86 football season that the dome project is “on hold.” Stated Reason: The federal tax reform bill is likely to make skybox leases non-deductible items, making them undesirable business expenses, especially for losing teams. “We’ve got to sit back and re-evaluate the entire project.” Actual reason: Byrne couldn’t raise the cash Olum required.

Dec 86 — Byrne, persuaded by Rich Brooks to do *something* about Autzen, gets approval from the state to begin some long-needed capital site improvements. To come: a new press box on the south side, luxury skyboxes and suites on the north side, and “a new athletic department next to the stadium”, which will eventually be the Cas Center, the first stage in the long-term project to eliminate the concept of parking at Autzen.

Byrne believes the success of these projects will make construction of the dome more likely.

**

As it turned out, the success of those other projects helped make the dome unnecessary. But the proposal never really died for several years.

The state never got serious traction on its bid for the Winter Olympics, removing the last external driver on the project. The dome became a political issue in 1988, when a Eugene legislator decided to make a flabbergasting push for the project. But by 1989, the projected cost had ballooned to first $21 million, then $30 million, and not even the combined support of the mayors of Eugene and Springfield and the local legislative team could get it going; at this point even Byrne had given up. And as late as 1993, Eugene city councilman Bobby Green, who played at Oregon in the early 70s, was interested in combining the dome project with a bowl game hosted by the university. By then, Byrne had moved on himself, to Nebraska.

Then, 1994 happened. And in 1995, Phil Knight hitched his star to the Duck wagon, the facilities went from worst-to-first, and eventually Byrne’s Folly was forgotten.

To Byrne, of course, the whole dome debacle was water off an erstwhile duck’s back. (It wasn’t the last time he’d throw himself under the Oregon bus for a concept. In 1988, he campaigned hard for a .01 tax on beer and cigarettes, with the proceeds dedicated to collegiate athletics; the ballot measure was crushed like an emptie at the polls.)

What of the dreaded Rain Theory, that Byrne blamed for costing the school thousands of dollars annually? After the Cal game in 1985, nobody could remember rain during an Oregon game until at least 1994, when there was a drizzle during the Arizona State contest in early November. Attendance for ASU was 41,693 — three bodies short of a sell-out. Maybe those last three seats would have been taken on a sunny day; we’ll never know.

Ultimately, the problem with the project became obvious: When it was thought to be needed, Oregon couldn’t afford it. When the football fortunes turned, not only was it no longer needed, the entire concept was considered absurd. Fans of a successful team don’t need to be motivated by the prospect of staying dry to attend games. And, as anyone who’s seen a late-season contest in the Carrier Dome recently can attest, a half-filled dome seems even lonelier than an open-air one.

Bill Byrne, 2006Bill Byrne accomplished a lot during his term at Oregon, and the fact that hardly anyone recalls the dome project today is testimony to his legacy. During his tenure, the athletic department made almost $19 million in physical improvements to UO athletic facilities, starting with the football practice fields across then-Centennial Blvd from Autzen, and ending with the Cas Center. Byrne rolled the dice on that first Independence Bowl bid, laying up-front cash for 14,000 tickets to secure the game because he knew you couldn’t get to a second bowl until you’d made the first one. Those dreaded paycheck games came to an end under Byrne’s watch, as did smoking in the stands, and — ironically — the use of umbrellas. And the Oregon Sports Network? Credit, or blame, Byrne for that concept as well.

Bill Byrne, 2006Bill Byrne accomplished a lot during his term at Oregon, and the fact that hardly anyone recalls the dome project today is testimony to his legacy. During his tenure, the athletic department made almost $19 million in physical improvements to UO athletic facilities, starting with the football practice fields across then-Centennial Blvd from Autzen, and ending with the Cas Center. Byrne rolled the dice on that first Independence Bowl bid, laying up-front cash for 14,000 tickets to secure the game because he knew you couldn’t get to a second bowl until you’d made the first one. Those dreaded paycheck games came to an end under Byrne’s watch, as did smoking in the stands, and — ironically — the use of umbrellas. And the Oregon Sports Network? Credit, or blame, Byrne for that concept as well.

Bill Byrne, the big thinker, can be forgiven for his dream.

And, anyway, it never rains at Autzen Stadium.

Jeff Tedford, former Fresno State QBYes, that Jeff Tedford. In 1982, Tedford was a first-year starter for Fresno State as a senior; he was a backup in the FSU win the previous year and didn’t see action then, but took over the starting job in mid-season and never gave it up. His favorite target, WR Henry Ellard, went on to enjoy a 15-year NFL career, including eleven seasons with the Rams and three Pro Bowl selections. Ellard set the NCAA season record for receiving yards in 1982 (1510).

Jeff Tedford, former Fresno State QBYes, that Jeff Tedford. In 1982, Tedford was a first-year starter for Fresno State as a senior; he was a backup in the FSU win the previous year and didn’t see action then, but took over the starting job in mid-season and never gave it up. His favorite target, WR Henry Ellard, went on to enjoy a 15-year NFL career, including eleven seasons with the Rams and three Pro Bowl selections. Ellard set the NCAA season record for receiving yards in 1982 (1510). benzduck | Comments Off |

benzduck | Comments Off |