A Brief History of the First Century of Oregon Football

(This is Duck Downs 101. Originally published on an Auburn fan site, Track’em Tigers. Revised and edited for general perspective.)

*****

The casual football fan is likely aware of a few basic facts about the Oregon Ducks:

1. They are from Oregon.

2. Their mascot is a duck.

The more involved fan may have a few more details, possibly including:

3. They are in the Pac-10 Conference.

4. The University of Oregon is in Eugene.

5. They were in the BCS championship game.

6. Their QB got kicked off the team last year and wound up at Ole Miss.

7. They got screwed out of going to the championship game in 2001, just like Auburn did in ‘04.

8. Their running back punched out that big fat Boise chump last year, which was AWESOME.

9. They are owned by Nike.

10. They really hate Washington for some reason.

11. “Animal House” was filmed there.

All of which is true, or at least true-ish. But ask the average football fan what they know about Oregon football in the 20th Century, and if you don’t hear crickets, you might get this kind of response:

a) They started playing football in 1994…

or

b) They used to really suck.

“a” is not true — it was 1894 — but we get it. And there’s no denying “b”. Oregon doesn’t have the kind of football history that a “traditional” team has. The Ducks were irrelevant for decades. That fact doesn’t make us bad, or inferior, just .. different. We’re relatively new at this whole “success” thing.

Consider that between 1960 and 1995, Oregon had only two of its 375 games televised nationally. Two games in 35 years. How about just six bowl appearances in the first 100 calendar years of existence?

And what other major college team played half its home games until 1967 in a 25,000 seat stadium over a hundred miles from its campus?

Yes, some of our players went on to great futures. There are NFL Hall of Famers in the alumni roster (Van Brocklin, Renfro, Fouts, Zimmerman). You might know that legendary NBC sports softball tosser, Ahmad Rashad, was a star tailback as Bobby Moore.

But there’s the rub. It’s more likely that a football fan knows a player is from Oregon, than anything about Oregon, especially pre-1994.

Knowing a little of what we’ve gone through might help you understand why some Oregon fans are a little crazy.

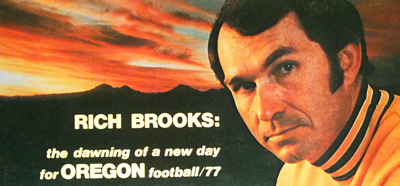

Rich Brooks, Oregon coach 1977-1994

Rich Brooks, Oregon coach 1977-1994

Consider this. Y’all have no doubt heard of Rich Brooks, who just retired last year from coaching at Kentucky. Well, Rich was our coach from 1977 through 1994, an 18 year period in which he went 91-109-4, and went to 4 bowl games, all of which were in the last 6 years of his term. After his one breakout season in 1994, when he finally won the conference, he bailed out for NFL money.

And the university named the field after him!

Think about it. What SEC school would keep around a coach for 18 years who only managed to win more than 6 games *twice* in his first 17 seasons? In Rich’s first six seasons, he only won 2 games 4 times, and wound up forfeiting the 12 victories he had in the other two years. He roundly criticized the UO administration for its failure to live up to promises made years earlier to update the lousiest facilities in the Pac-10. He’d talk up his teams pre-season, and then coach them to losses against teams like Fresno State and Pacific.

Brooks was a stubborn caretaker who loved his players, hired quality help, and refused to lose, even when he lost. And we kept him. Because the culture in Eugene in the last half of the century wasn’t one that celebrated college football. All that we expected was that it earn at least make enough money to pay for the other programs that qualified us to stay in the Pac-10. And win a home game or two. Some years, the Ducks could barely do that.

I grew up in Eugene. I was a Boy Scout usher in ‘68 and ‘69 at Autzen Stadium. The fact that Oregon used teenaged boys in dorky uniforms for crowd control back then should tell you something about the crowd, and the culture. And that culture, I believe, helped keep Oregon football down for so long. (Think Vanderbilt, with more hippies and not quite the academic standards.)

***

Since most “modern” college football histories use WWII as a dividing line, that’s a good place to begin. Oregon was at least a competitive program in the post-war years. There weren’t a lot of bowl bids, because back then there weren’t a lot of BOWLS, and they were mostly back in your neck of the woods, and they didn’t like to invite teams from the West because it was hard for fans to get to the games.

Norm Van Brocklin. “The Dutchman.”

Norm Van Brocklin. “The Dutchman.”

The really good teams weren’t ignored. Norm Van Brocklin led the ‘48 team to a 9-2 record and the Cotton Bowl, where they lost to Doak Walker and SMU. This being Oregon, we only won seven games over the next three years. After Jim Aiken’s last team went 1-9 in 1950, still the worst record in Duck football history, a coaching change brought Len Casanova to the sidelines from Pitt.

“Cas” is one of the titans of Oregon football. His name is on the athletic department building. Everybody loved Cas.

And he took us to three bowls in 16 seasons.

Culture.

Cas’ biggest success was making the Rose Bowl, after the 1957 season, where Jack Crabtree and Jack Morris led a 7-3 Duck team in a heroic effort against #1 Ohio State, losing 10-7. (Some take great glee in pointing out that Oregon hasn’t won a Rose Bowl since 1917. For the most part, these are Washington fans, to whom ancient history is everything.)

This is where the story starts to get interesting, in a “Damn, why did y’all put up with that for so long?” way.

In 1959, thanks to the machinations of other conference members after the original Pacific Coast Conference imploded amid widespread NCAA sanctions, Oregon found itself as an independent. There was moderate success — a Liberty Bowl bid, against Penn State, in 1960 (another loss); and a Sun Bowl bid in 1963, a win — the first Oregon bowl victory since 1917! — over a 4-6 SMU team that was only in the game because no qualified team was available.

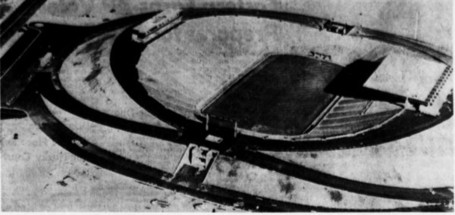

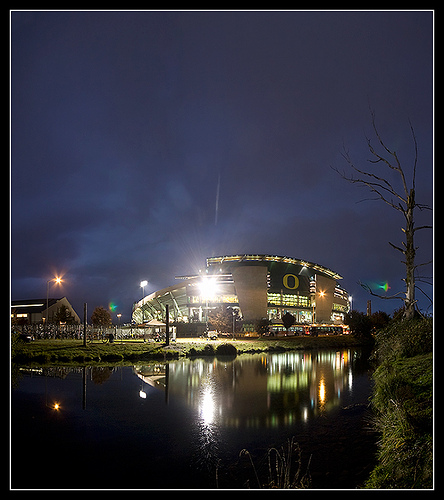

By 1964, the Ducks were back with their old conference mates in the new Pacific Eight Conference. For Oregon football, the decade of the ’60s was consumed with struggling to keep up with the titans of the new Pac-8 — USC and UCLA, the only teams you ever saw on TV. As college football grew in popularity, it became clear that Hayward Field, the on-campus stadium, was far too small at 23,500 seats to host a major college team. Half the home games were actually played 110 miles up the road, in Portland, including the Border War with UW. In an attempt to keep up with the conference leaders, a new stadium was proposed and built. It cost about $2.5 million, seated 42,000, and was named “Autzen Stadium” after the timber baron who donated $250,000 to get the project off the ground, across the Willamette River from the UO campus.

Autzen Stadium, newly completed, summer 1967

Autzen Stadium, newly completed, summer 1967

Autzen opened in 1967. Oregon had a new coach, Jerry Frei, who struggled under the legacy of his predecessor, Len Casanova, who had moved on to AD. Progress was gradual. 2-8, then 4-6. But Frei was a solid coach who eventually found a career as an NFL assistant. He had the right ideas, and was building a Program. Recruiting the West heavily, he brought a speedy back named Bobby Moore in from Tacoma; you know him now as Ahmad Rashad, the softballing NBC commentator. Then, he landed Dan Fouts out of San Francisco.

Things started clicking. The ‘69 Duck team was highly competitive, just 8 points from going 8-2. The ‘70 team had our first winning season in 6 years, and was ranked as high as AP#16 after a win over USC.

But Frei had a problem. He couldn’t beat the aggie school up the road. And in the state of Oregon, nothing defined a team more than the Civil War results. Since 1958, in fact, Oregon’s record against OSU was a pathetic 1-11-1. The boosters expected that ‘71 would, at last, be the year the Ducks took back the state from the damn barkrats.

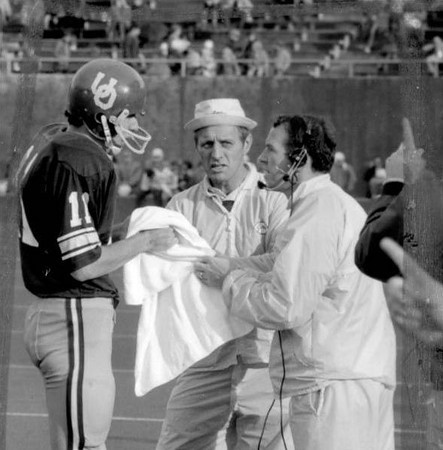

Dan Fouts, Jerry Frei, Bruce Snyder, 1971

Dan Fouts, Jerry Frei, Bruce Snyder, 1971

Frei called the 1971 Civil War game the most important of his life.

The ‘71 Ducks lost to the Beavers at Autzen again, 30-29, securing another losing season at 5-6.

A month later, Frei, under pressure to sack some assistant coaches that certain Portland-area boosters considered incompetent, and without any show of support from his basketball-friendly athletic director, resigned. Among the members of Frei’s incompetent coaching staff were John Robinson, George Seifert, Bruce Snyder, John Marshall, and Dick Enright.

Guess who got promoted? Naturally, Enright was deemed the competent one in the bunch, and was named Oregon’s new head coach.

The period of Oregon football history known as The Suffering had begun.

***

Call it a curse, or bad karma. Call it getting what you expect. Call it getting what you pay for. The bottom line is that between 1971 and 1994, Oregon Football was irrelevant to all but around twenty thousand of its most interested fans. The only others who cared were members of the local media, who were paid and thus under obligation to pay attention to them; the student-athletes themselves, who were at least getting a free education, and their families; and others under direct employ of the UO. That makes for a limited support base. Combine this with the fact that there was a lot more to do in the Eugene area in 1972 besides paying to watch bad football in the rain and it’s not hard to see what the Ducks were up against back in the day.

From whom little is expected, little is returned. Enright’s career lasted two years. He was a “player’s coach”, a good recruiter at a school that didn’t have a recruiting budget, but a lax disciplinarian and a poor tactician. Enright did finally break the OSU curse, winning the Civil War 30-3. But his team was blown out 68-3 at Oklahoma, and 65-20 at UCLA, and not even beating the Huskies 58-0 in ‘73 could save his job, after losing at home to OSU and going 2-9. Out went Enright. (Warning: Do *not* search the internet for Images using “Dick Enright.”)

In came Don Read, a cerebral genius and quarterback guru and genuinely nice guy. Read would eventually find his footing at Montana, leading the Griz to a 1AA national championship. But at Oregon, in the Pac-8, he was simply over his head. Some of Oregon’s most legendary beatdowns occured on his watch. It didn’t help that the athletic director continued to support those paycheck games against the national powers in an effort to balance the budget.

His first game was at Nebraska. Ducks lost, 61-7. More blowouts followed. 40-10 to Cal. 66-0, to a terrible UW team. 35-17 to the Beavers.

In ‘75, the bottom fell out.

Anonymous UO back meets Oklahoma defense, 1975

Anonymous UO back meets Oklahoma defense, 1975

Another paycheck-game blowout at Oklahoma (62-7) was followed by a loss in the home opener.. 5-0, to San Jose State. Yes, football, not baseball. Afterward, new Oregon President William Boyd famously declared “I’d rather be whipped in a public square than watch a game like that.” Fans agreed. The announced paid attendance in ‘75 averaged just over 22,000 per game, a gross overestimate. In the ultimate insult to tradition, official Homecoming festivities were cancelled in 1975; who wanted to come home to this?

The losing streak eventually reached 14 games, finally ending where it started, with a win over a Utah team that finished 1-10. The victory was witnessed by just 10,500 true-green fans, an Autzen record that will almost certainly live forever.

Read, despite a modest upgrade in his recruiting budget, kept telling the Oregon Club that we just couldn’t compete with the “big schools” for top players, so, he wasn’t going to bother trying. He had it backwards, of course.

After 1976, when USC blew the Ducks out of Autzen, 53-0, and another paycheck loss at Notre Dame (41-0) was the highlight of a six-game losing streak, not even another win against OSU could save Read’s job.

***

There was a nationwide search. Bill Walsh was offered the job, but turned it down for Stanford. The desired qualities sought eventually devolved to “anybody stubborn enough to take THIS job for $32,000 a year.” In the end, it fell to Rich Brooks, a UCLA assistant coach and — horrors! — OSU graduate.

The Brooks era did not begin auspiciously. For one thing, Rich had the honor of taking his team into the SEC for not one but *two* paycheck games, including his season opener at Athens. The team kept it respectable, losing by 11, then got his first win as a head coach at moribund TCU. But the beatdowns resumed; 8 straight losses, average score 40-11. He did get a win over OSU in his first try, though.

Another 2-9 year followed. They started 0-7, including a home loss to TCU, a team that hadn’t won a road game since Nixon was president. But the last 5 losses were by a total of 17 points, which was a lot better than being blown out. Progress.

And Brooks was starting to see the results of an upgrade in recruiting. He’d pounded the table, insisting on a higher recruiting budget. He hired John Becker as his offensive coordinator, and made him the highest-paid assistant in the conference. Becker had coached at a juco in Los Angeles and knew the good players, and brought some along with him. There was finally real talent in the backfield, and size in the trenches.

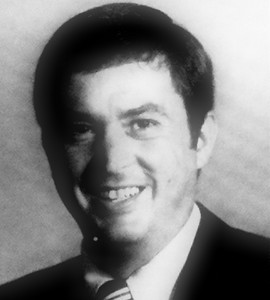

Reggie Ogburn, Oregon QB 1979 - 80

Reggie Ogburn, Oregon QB 1979 - 80

In ‘79, dual-threat juco transfer Reggie Ogburn chose Oregon over Cal, and with him at QB the Ducks had their first winning season in 10 years, going 6-5. The city went nuts. Home attendance was up 35%. 1980 was going to be The Year of the Duck.

Then… thud. It turned out that one of Becker’s qualities was his ability to get players academically eligible without attending all those silly classes. And the culture of the team had suddenly become sadly similar to that at some of the big-boy schools; a group of talented players thought they could get away with anything they wanted. Brooks had gambled, and lost one of the few qualities his predecessor possessed - integrity.

Caught up in the national pay-for-credits scandal, and with players accused of crimes ranging from phone-card theft to burglary to sodomy, the ‘80 Ducks played under probation. Ineligible for bowls, with some star players sidelined, they still managed to go 6-3-2, with a blowout win at Washington. Still, attendance was up again. Fans liked winners. Who knew?

One more year of probation. Plenty of talent returning for ‘81. The Quack was Back. Brooks challenged reporters to put his 1981 team in the Top 20. He was confident of winning seven, maybe eight games, and challenging for the Rose Bowl.

Oregon lost the first game of 1981. To Fresno State.

They wound up 2-9. Nobody voted them into the Top 20. They were, however, fixtures in Steve Harvey’s Bottom Ten.

In 1982, they lost to Fresno again, this time at Autzen, 10-4. (The score, not the CB lingo.) Only an inexplicable tie with Notre Dame salvaged another 2-win season. Sure, they beat OSU again, but that was now expected; in fact, Brooks had never lost a Civil War game, as a player, an OSU assistant, or as Oregon’s head coach. A solid faction of boosters would have kept him employed for life at Oregon just for that.

1983 opened with another loss. At home. To Pacific, which would drop football altogether a few years later. The season ended with the infamous Toilet Bowl, the 0-0 Civil War turdfest that was the last scoreless tie ever in Division 1 football. And yet, many fans in Eugene, by now among the most patient in America, considered 4-6-1 great progress.

In fact, 1983 was the year Oregon transitioned from “general suckitude” to “solid mediocrity.” The Ducks went 6-5, 5-6, 5-6, 6-5, 6-6 between ‘84 and ‘88. And new NCAA regulations limiting scholarships and traveling roster sizes, along with increased support generated by a sharp young athletic director named Bill Byrne, were helping Brooks become more competitive on the field and on the recruiting trail.

Bill Byrne, UO Athletic Director, 1983-92; Savior of Oregon Football

Bill Byrne, UO Athletic Director, 1983-92; Savior of Oregon Football

Byrne gets credit for ending the dependence on paycheck games, and finally coming through with the facilities upgrades that Brooks had been begging for. Yes, he had the crazy idea of putting a dome over Autzen, but a lot of people in Eugene thought it was a good idea at the time.

In 1987, after a 4-1 start capped by wins over ranked Washington and USC, Oregon was ranked AP#19. It was the first national ranking since 1970. The team celebrated by losing its next four games.

In 1988, an even better start. 6-1 after another win over the Huskies. Then, QB Bill Musgrave decided to attempt to tackle an ASU linebacker with his collarbone. Crack went the shoulder, and Musgrave and the Ducks were done for the season, with five straight losses.

Still, the Bill Musgrave Era marked a change. The strong-armed QB would finally lead Oregon in 1989 to its first 8-win season in decades and its first bowl bid since ‘63. Okay, it was the Poulan Weed-Eater Independence Bowl, in Shreveport, against Tulsa, and it cost the school a fortune in guaranteed tickets, but it was a BOWL GAME DAMMIT! Which they WON. The cherry was popped. Success was imminent! Respect was demanded!

As a senior, Musgrave took the Ducks to another 8 wins, and another bowl, the Freedom, against Colorado State. They lost a heartbreaker.

Bill Musgrave graduated, having broken Dan Fouts’ season and career passing records. The team returned to mediocrity. ‘91 saw a 2-0 start, but a 1-8 finish. And, somehow, Brooks started losing to OSU again, twice in three years. Injuries mounted. We were back to being just another .500 team, struggling to beat the Beavers and win more than a few conference games. Attendance was still high, but the natives were getting restless. A return to the Independence Bowl in ‘92 didn’t exactly energize the fan base… especially when they lost to Wake Forest.

By the end of 1993, Brooks was on the hot seat. Oregon had blown a 30-0 lead at Cal, losing 42-41, and another promising 3-0 start turned into a 5-6 downer. The coach had recently been named athletic director, in an obvious attempt to save money, and around Eugene fans were asking when Brooks would get around to firing himself.

In 1994, after 3 games, Oregon was 1-2 and had just lost to Hawaii and Utah — at home. Now the sharks were circling. Now, after 17 seasons, Brooks had reached the end of his rope. Iowa was coming to Eugene to put him out of his misery.

Oregon beat the Hawkeyes 40-16. They went 8-1 to close out the season and win the conference; the tipping point was a dramatic win over AP#6 Washington at Autzen, that featured a play frequently considered kind of memorable…

The Ducks were in the Rose Bowl again, as a writer for the LA Times put it, “every 37 years, just like clockwork.”

The Suffering was over. Brooks took the money and ran to the NFL. But the cupboard wasn’t bare. Offensive coordinator Mike Bellotti stepped in as head coach. Oregon’s richest fan, Nike head Phil Knight, started pouring his personal fortune into facility improvements, and made the Ducks his company’s featured client.. and the rest is history, and well documented on other fan sites and the general media.

Since 1994, Oregon’s only seen one losing season (2004, 5-6). Only missed post-season play twice. Won ten games or more 7 times. Finished ranked in the AP Top 25 eleven times. Won or shared the Pac-10 title five times. Hasn’t lost to Washington in seven years (average score, 43-17). Etc.

Despite the 2002 expansion to over 58,000 seats, Autzen Stadium has been sold out for every game since 2004. Oregon has the best facilities in the Pac-10, rivaling any in the country, and they just keep improving.

A significant majority of current Oregon fans jumped on the bandwagon in 1994. Who can blame them for sitting out the years of suck? But for those of us who lived through The Suffering, the recent success of our beloved Ducks is just mind-boggling.

The old saying is “I’ve been rich and I’ve been poor, and rich is better.” Are Duck fans who stuck with the team through twenty years of bad football more legitimate than the ones who jumped on in 1994? No.. but you’ll have to forgive us for thinking we appreciate it a little more than they do.

benzduck

benzduck